I put out a survey and talked to a lot of Firearms Instructors about the most consistently unreliable pistols they’ve seen come through their classes. When the pattern emerged through the Signal/Noise filters, it confirmed my theory. Short Barreled 1911’s are the Most Unreliable. Let’s look at this for a second and see why.

The 1911 family of guns tend to be very reliable. During the Pistol Trials before the gun was adopted by the US Army, the Colt ran well over 6,000 without problems and thoroughly crushed the competition (Savage) which didn’t even make it halfway. Since then, it garnered a reputation for being unreliable? What happened?

Well, for a long time, Colt owned the patent on the design and if a 1911 wasn’t built by Colt, it was built under license and the guns all tended to follow that pattern rather closely.

Then the gates opened and anyone could build 1911 pistols… and anyone did. Everyone did. And the term 1911 became akin to the term “Pickup Truck”. Saying Pickup Truck is only telling me the STYLE of the vehicle, not make, model, year, engine option and trim package… So Many Variations on that Theme! The 1911 is very much like that today. The only real characteristics of a 1911 are the Slab Side styling, Single Action trigger mechanism with twin push bars, and locking lugs that are cut in front of the chamber that match cuts in the slide. Now, even these characteristics are flexible as we’ve seen Double Action and Safe Action type 1911’s… it’s all very confusing to the newcomer. Along with all these variations are alterations to the 1911 blueprint in terms of dimensions and tolerances.

Now, back in 1976 a company called Detonics came out with a 1911 called the Combat Master. I have articles on the Combat Master here, and another one published in Concealed Carry Magazine here. Great little pistol that did pretty well. After Detonics came other companies trying to make super short barreled 1911 pistols… Kimber is the most famous for this with their “Ultra” series. Other’s followed that example due to the popularity of the concept, a super small 1911 for Concealed Carry. Great! The problem was that none of these really worked as well as the Combat Master and even the later Combat Masters didn’t work as well.

I’m going to lay it out here… I’ve never had an Ultra 1911 pistol, or any 1911 pistol with a barrel length under four inches get through any of the Training Courses that I taught without any problems. Furthermore, I’ve never been in a Training Course that had such a pistol get through the course without problems.

Double Feeds. Failures to Fire. Failures to Eject. Failures to Extract. Stovepipes.

So what’s the problem? Bad Gun Hygiene? Are the guns too dirty? Are they too dry? Bad Ammo? Certainly, all those are contributing factors. But to truly understand the problem, one must come to an understanding of how the 1911 functions.

Let’s watch this Vickers Tactical Video. Larry and his Team made a great video with some boss slow motion so you can really see what’s going on here. I want you to pay attention to the Cartridges. Go ahead, watch that video… We’ll wait.

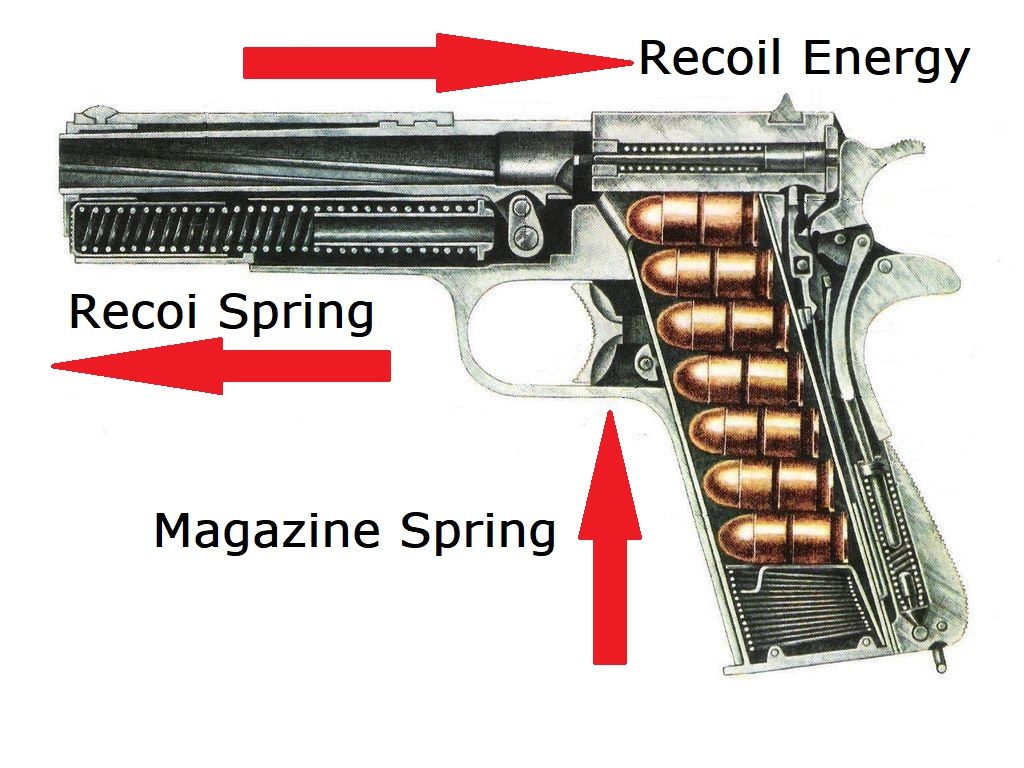

Notice how the Empty Brass can kind of just dance around the ejection port… And notice how it takes a space of time for the next cartridge in the magazine to come up inline and be ready to feed into the chamber. We’re looking at what happens within the span of time called “Dwell Time”. And with the proper 5 inch barrel 1911, that Dwell Time gives ample time for full extraction, ejection and feeding. When you shorten the 1911’s barrel and slide, it changes the timing, and can shorten that dwell time. Typically, going down to 4.25 inches, what’s called “Commander Length” is no problem. Going down to a flat 4 inches is usually also not a problem. But when you go down to 3.5 inches… That Dwell Time is reduced to the point that reliability is compromised. This is why you can see the pistol’s slide Short Stroke or Stove Pipe and all these reliability issues come bubbling to the surface. Because it all comes down to balance. There are three factors in the balance that gives us Dwell Time… Recoil Energy pushing the slide back, the Recoil Spring energy pushing the slide forward, and the Magazine Spring pushing the next round up.

A shorter slide is lighter, so it moves rearward quicker. A shorter barrel doesn’t allow enough retained energy to get that slide moving fully to the rear. That lighter slide then starts to move forward quicker as there’s less inertia to hold it open long enough. The Dwell Time is just not enough, and now you have a less reliable pistol.

You can try overcoming this by running Heavy For Caliber type loads. Full 230 grain projectiles (in .45 Auto) that are loaded to full spec pressures should go a long way. But lighter loaded promotional ammo (Cheap Bulk) might not do it… You need Pressure to give you that inertial energy needed to fully cycle a semi-auto action. This balanced with Spring Weights can have a big impact on that Dwell Time that you need to maximize. All Semi Auto Pistols have the same factors for reliability… but not all Semi Auto Pistols have compromised designs to fit fashion trends like a Kimber Ultra.

The other least reliable pistol was pretty much “Anything from Brazil”. But that’s another article.

What about the shorter barreled 1911 types but chambered in 9mm? Same issues?

They can if the makers just start out with a standard 1911 and didn’t adjust spring rates properly for the shorter barrel as they do with the full 5 inch version. The physics is the same.

In my experience the 9mms run significantly better. The newer Colt Defenders seem to run the best, though the 9mm Kimbers are pretty good too

The lower recoil impulse and the more forward presentation of the case to the breach face really help.

The problem with short barreled 1911 dwell time, besides the simple loss of mass from the slide/barrel assembly reducing inertia and thus speeding up the cycle time and requiring heavier springing, etc, is that as you shorten the slide you lose space to cram the recoil assembly and the channels for the slide rails in there. Since no one seems inclined to re-engineer the frame to have shorter slide rails, the end result is not only do they have less dwell time because the slide moves faster, they have less dwell time because the slide doesn’t move -as far-. This is easily observable by hand: pull a 5″ 1911 slide back as far as it will go, and look in the ejection port. The disconnector tip will be visible forward of the breech face. Now pull a 3.5″ or 4″ 1911 slide back as far as it will go, and look inside. The breech face almost certainly will not be far enough to the rear to uncover the disconnector, and on a 3.5″ or less gun the breech face may just be behind the magazine channel by a fraction of an inch! This reduction in travel has far more dramatic effects on timing and reliability than the mass reduction does, assuming the respringing has been done conscientiously.

Detonics Combat Masters worked really well as shortened 1911s go because they put a lot of effort into designing and refining the recoil assembly, first of all, but also because Detonics was literally cutting down full sized guns and not losing as much slide travel.

That’s correct. The balance of the spring rates is a problem that most makers do not want to deal with, so they just smooth up the rails and hope for the best. If you send the gun back in, often they will polish feed ramps, and then hope for the best when they send it back to you. Simply dropping in a 2 pound heavier recoil spring can often times just aggravate the problem.

It also means the slide has less time to accelerate and stop a round from the magazine.

Had a Combat Master in .45 ACP in the late 70’s and it was reliable but nearly uncontrollable. Couldn’t hit the broad side of the barn from the inside.

Good stuff & sweet video.

Two factors not mentioned, that go hand-in-hand:

1. Recoil of particular cartridge

2. Stability of grip/base

Having owned some guns on the edge of the physics envelope for function ( Kel-Tec P-40 .40S&W 14oz especially), I have observed that smaller/lighter pistols have less tolerance for a less-than-good grip(1) and that a heavier-recoiling cartridge on the same platform exacerbates this.

When it came time for my family to purchase a clone of the Officer’s ACP (3.5″ bbl) , I ditched .45ACP and ran with a 9mm variant. Even my wife can run it without jamming. Doesn’t hurt that it has a smidge more mass in the bbl than the .45ACP variant. It runs lighter springs than the .45ACP variant and I would bet dollars to donuts that the slide moves through its operating range at a slower velocity. We run 135gr standard pressure 9mm in the magazines.

And I replace the recoil and mag springs periodically to keep them fresh. The OACP is a compromise design and I don’t want the springs to fall outside their design envelope.

.

.

.

(1) “Less-than-good” grip being a function of both technique and the mass of the shooter and his meat hooks. Bigger boys with bigger paws can get away with poorer technique and keep the gun running. Newton’s Third Law can’t be bribed into looking the other way.

Correct. In some 1911 style pistols the design has been successfully reduced to about 85% of the original size and chambered in the .380 ACP but in those pistols the relationship between the parts remains almost identical to the original design so they seem to work well. Again, a firm hold reduces the chance of malfunctions.

My old series 70 Combat Commander is still my most reliable 1911 style pistol and the upgrades are mostly cosmetic. A little judicious polishing of the feed ramp and tuning the trigger is all its ever had done to it aside from keeping the springs fresh and occasionally re – tensioning the extractor.